Wind River still flows on Intel, but it's forked into Arm

Randy Cox of Wind River says inline accelerators are compatible with virtualization and cloud-native architecture, but he doubts they're genuinely open.

Intel remains a harsh critic of using extra silicon, hosted on cards separate from the main server, to support most physical-layer functions in a virtual radio access network (RAN). Commercially, that's no surprise. The big chipmaker has an obvious interest in keeping as much as possible on its central processing units (CPUs). But it seems to have a point. Custom silicon needs custom software, making the whole setup harder to manage on a single platform.

That's not a view shared by Wind River, one of several companies in that software-management business. It spent about nine years under Intel's ownership but diverges from its former parent on the matter of RAN acceleration. Inline, the offload-everything technique slammed by Intel, is just as manageable as lookaside, where an extra silicon accelerator is used for just one or two awkwardly demanding functions, according to Randy Cox, Wind River's vice president of product management for the intelligent cloud.

"We support Intel in terms of their architecture, and we support Marvell in terms of their architecture," he said, throwing out the name of a prominent inline backer chosen by Nokia as a cloud RAN supplier. Cox, who spent ten years at Nokia before joining Wind River in July 2021, understands why Marvell, which licenses chip designs from UK-based Arm, was a natural fit for the Finns and their physical-layer (also called Layer 1 or just L1) software.

"They pride themselves on their L1 software and are not going to give that up, and they have used Marvell in their traditional product," he told Light Reading. "They will use a Marvell chipset because they want to reuse their L1 software as their differentiation. As soon as I came on board, the first thing I said was, 'let's get engaged with Marvell and enable this on our platform.'"

Intel laid out its objections to the heavy use of custom silicon in a recent white paper. When nearly all functions live on one of its general-purpose processors, almost all RAN software can be coded in the same programming language. Custom silicon, by contrast, often comes with proprietary languages and other tools. Yet Cox is not persuaded. "I'm not sure I understand the argument that it's not virtualized," he said. "The RAN workload is containerized."

Stormy RAN waters

This is where Wind River sweeps in as one of a small number of "containers-as-a-service" players. Each provides the apparatus needed to run network and IT workloads in various public and private clouds, using tools such as Kubernetes – the de facto open-source platform for managing the "containerized" cloud-native software that Cox highlights.

Wind River's support for inline accelerators is therefore critical, and it provides validation of claims recently made by other companies waving around accelerator cards like tickets to a show. Among them is chipmaker Qualcomm, another Arm licensee, which also says it has started to work with Wind River on RAN virtualization.

Gerardo Giaretta, Qualcomm's general manager of 5G RAN infrastructure, is similarly dismissive of Intel's argument that inline accelerator cards are incompatible with virtualization. "You have this concept of physical and virtual functions, but the physical functions can be updated and managed by the virtualization layer and so that argument has short legs," he said during a recent interview.

Even so, his comments acknowledge there are physical functions in the mix, and there are still no commercial deployments to assess. Intel seems to have a valid complaint about custom L1 silicon relying heavily on digital signal processors (DSPs) that use proprietary code. Until now, most of the underlying technology has come from just two companies – CEVA and Cadence Design Systems (through its $380 million acquisition of Tensilica in 2013).

The proprietary nature of the technology is clear from CEVA's own description. "Platforms typically integrate a CEVA DSP core, hardware accelerators and coprocessors, optimized software, libraries and tool chain," said the company in its last annual filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Few people specialize in this type of software programming and code would have to be rewritten if the vendor switched to a different architecture, Intel argues in its white paper.

But Giaretta insists the industry's familiarity with CEVA and Cadence means there is less risk than Intel implies. "That part of the software can still be implemented in a pretty open way in an inline accelerator," he said. "Our solution uses DSPs that are not Qualcomm-specific and have a tool chain that is very common to the others."

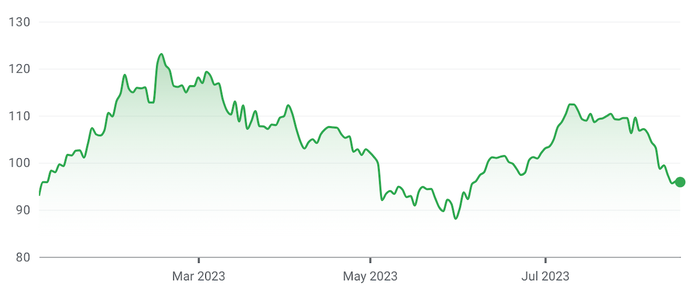

Share-price performance of Aptiv, Wind River's parent, this year ($) (Source: Google Finance)

(Source: Google Finance)

Still, Cox is not entirely opposed to Intel's rationale. The tight coupling of hardware and software puts inline accelerators at odds with the notion of open RAN (or O-RAN), he concedes. "If you want to argue that it's not O-RAN because you are not using someone else's L1, I mean, yes, I would agree with that," he said. "But I don't think there is anything wrong with that. There are pros and cons both ways."

With open RAN, elements are supposed to come from different suppliers and be totally swappable. Qualcomm supplies both hardware and software with its L1 inline accelerators, while Nokia has taken the same approach it used for purpose-built RAN products, where its software is married to Marvell's chips. "Typically, inline solutions use energy-efficient Arm-based silicon that is also commonly used in classic RAN networks and increasingly across all networks, including webscalers' cloud data centers," said the Finnish vendor in a recent white paper.

Branching off

Besides voicing approval of inline accelerators, Wind River has also begun to provide support for Arm as the CPU in virtual RAN deployments. In this scenario, an Arm licensee would replace Intel not just in L1 processing but for other network functions, too. Intel remains dominant in this small virtual RAN sector today, thanks largely to its historical success in server CPUs, where last year it had a 71% market share, according to Counterpoint Research. But Arm is on the offensive, and Cox sees it as a creditable alternative to Wind River's former parent.

"We have done initial integration of Wind River Studio, via the open-source StarlingX project, on an Arm platform and we're moving forward in that space because we see the benefits of Arm," he said. "Of course, Intel has a pretty good headstart here in terms of the RAN, but we definitely see advantages with Arm and have a very close relationship with Arm and are moving forward with some Arm-based vendors to progress that even further."

Work has started with various companies here, including Softbank, Arm's current owner; chipmaker Nvidia, which uses Arm designs for its own Grace-branded CPUs; Japanese 5G equipment maker NEC, which is also working with Qualcomm on inline accelerators; and HPE, a manufacturer of computer equipment that is developing an Arm-based server for the RAN in partnership with Ampere Computing, an Oracle-backed chipmaker.

Cox says most of the underlying development work has been done and that it did not require a huge amount of "heavy lifting" by core engineering teams. The next step would be the actual commercialization of a product. "We're waiting for the first customer to come along to make that happen and we will be in a good position because all this upfront work has been done."

Arm is typically lauded for the energy efficiency of its architecture, but catching Intel may be tough. Recent gains in the bigger market for server CPUs have gone mainly to AMD, which uses the same x86 architecture. Arm "cores," the building blocks of the microprocessor, are less powerful than x86 ones, according to an industry expert, meaning Arm licensees have even greater need of accelerators.

Ampere, AWS and Nvidia, the three most prominent developers of RAN silicon based on Arm blueprints, all seem to prefer inline to lookaside – whether provided on a separate card or more closely integrated with the CPU. If operators buy those Intel arguments, and are determined to make use of lookaside, it could be a problem for Arm. Having tributaries that course through both camps seems like a sensible approach by Wind River.

Related posts:

— Iain Morris, International Editor, Light Reading

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

_International_Software_Products.jpeg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)