The death of open RAN and why fewer vendors might be a good thing

The specialists have given up specializing and the giants have continued to land the biggest deals.

_%E2%80%93_Vienna_Museum.jpg?width=850&auto=webp&quality=95&format=jpg&disable=upscale)

A gruesome crime has been committed – the bludgeoning and mutilation of the open radio access network (RAN) concept by some of its purported sponsors. For sheer drama and historic importance, it's not quite up there with the stabbing of Julius Caesar (see image above) by people he considered friends. But if open RAN had a voice, it might be gasping "et tu, AT&T" with pained breaths.

It had promised to be the standardized joinery holding together different vendors at the same mobile site. This would supposedly benefit makers of specific parts, previously ignored by telcos because they could not supply all the furniture. The joinery is showing up, but it usually connects the same vendor's pieces, as in the $14 billion deal between AT&T and Ericsson announced in December. The specialists open RAN should have helped with their specialisms have instead morphed into "end-to-end" suppliers with a full set of products – miniature versions of Ericsson.

Open RAN's staunchest supporters are meanwhile in denial, like certain victims of trauma, or Monty Python's Black Knight, insisting on his good health as he is sliced up. The concept is alive and well, having already produced a thriving ecosystem of vendors and broadened choice for telcos beyond the usual suspects of Ericsson, Huawei and Nokia, they say. Evidence shows the opposite. The only big change has been Huawei's elimination from some western markets, after a geopolitical backlash against China, and the rise of Samsung as an alternative. But this could easily have happened without open RAN.

Living in denial

Data from trusted research authorities is incontrovertible. The market share of the top seven telecom equipment vendors – Huawei, Nokia, Ericsson, ZTE, Cisco, Ciena and Samsung – was unchanged at 80% between 2022 and 2023, says Dell'Oro. In the RAN sector, the share of the top five vendors – Huawei, Ericsson, Nokia, ZTE and Samsung – shrank just 0.5% between 2021 and 2022, to 94.6%, according to a detailed report from Omdia (a Light Reading sister company) published last year.

This others' share of 5.4% equated to revenues of just $2.4 billion (excluding services), split between numerous companies that gave up specializing, and expanded their product portfolios, as the RAN market shrank. Total market revenues dropped 11% between 2022 and 2023, to about $40 billion. Maintaining sales at $2.4 billion would have required market share growth to 6%. And this year, Omdia forecasts a decline in RAN sales of between 4% and 6%.

Unsurprisingly, the "upcoming vendors" cited by Omdia are in bad shape. Revenues at Airspan, given a 0.5% share of the RAN market by Dell'Oro in 2022, plummeted 43% for the first nine months of 2023, to $71.1 million. Its share price has dropped like Wile E. Coyote off a cartoon cliff since August 2021, falling 98.8%. In December, Japan's NEC slashed its 5G revenue forecast outside Japan by 64%, to 31 billion Japanese yen (US$200 million) in 2026. This year, it expects that global 5G business to record a JPY10 billion ($66 million) loss. Fujitsu blamed "weakness" at its network products business in North America and Japan for a 45% year-over-year drop in third-quarter operating profit, to JPY19.6 billion ($130 million).

Airspan share price (US$) on New York Stock Exchange (Source: Google Finance)

Other early champions of open RAN are also bleeding. Rakuten Symphony, which sells various network software products and services, reported a 30% drop in recent fourth-quarter sales, to $161 million. Parallel Wireless reportedly laid off hundreds of employees in 2022 and is no longer seen as a viable contender by Vodafone, which previously trialled its technology.

Less certain are the fortunes of privately owned Mavenir, which has enjoyed a degree of success in the market for core network products. But Laurent Leboucher, the group chief technology officer of Orange, explicitly named Mavenir when he recently said it was "not clear" how smaller vendors could be a part of open RAN initiatives.

Broken promises

Some would have stood more chance if the original multivendor promise had survived. A specialist can stake its entire research-and-development (R&D) budget on one technology square. A jack-of-all-trades must spread the bet. It must either dilute the earlier focus or commit a bigger percentage of sales to R&D in a contracting sector. And profits are already thin. The operating margin at Ericsson's mobile networks business shrank from 20% in 2022 to about 11% last year. Nokia's equivalent figure fell from 8.8% to 7.4% over the same period.

This is precisely why open RAN was conceived. Industry folk naturally assumed the smaller companies with limited resources would be outmuscled by the industry giants if forced to compete for single-vendor contracts. With the passing of open RAN as a genuine aid to specialists, and its survival as a tokenistic set of interfaces, that assumption is proving correct.

The RAN market was previously unable to sustain more than a handful of suppliers, losing names such as Alcatel, Lucent, Motorola and Nortel in several rounds of merger activity. It now appears ripe for consolidation once again. Nor, in the context of technology globalization, would it look unusual with fewer players. Telcos regularly deal with only three big public clouds and two smartphone operating systems. The chips in their most advanced basestations are manufactured by just a couple of Asian foundries. The obsession with bringing a multiplicity of suppliers into the RAN seems bizarre.

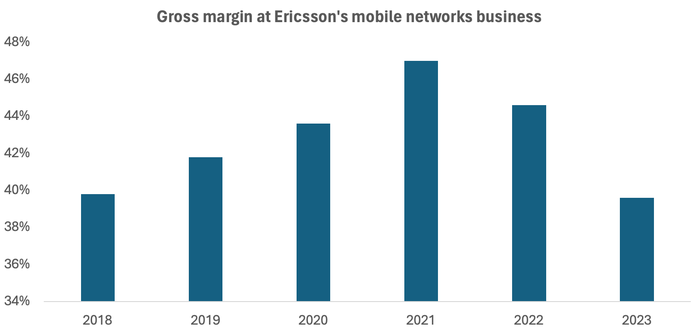

Would consolidation today necessarily be a negative? A geopolitically influenced, Soviet-style engineering of the market by governmental authorities and telcos has undoubtedly produced inefficiencies. Telcos wanted to drive down prices, and lower their costs, by introducing new competitors. Yet there is scant evidence within the financial results of Ericsson and Nokia that telcos are being gouged. The gross margin at Ericsson's mobile networks business fell by 7.4 percentage points between 2021 and 2023, to 39.8%, and is at its lowest level in six years. Nvidia's gross margin, by contrast, has risen more than 10 percentage points in just one year, to 77%.

(Source: Ericsson)

For European operators keen to have supplier choice in their own backyard, a further weakening of the most trusted vendors could backfire. Between them, Ericsson and Nokia have outlined plans for up to 23,000 job cuts since early 2023, about 12% of the combined total for 2022. Restructuring at Nokia has already given each business group more autonomy and independence from the rest of the organization. There is speculation this could precede a spin-off or sale of mobile infrastructure assets to a US investor, and the subsequent relocation of the mobile networks business group to North America.

But this would unnerve customers that have already watched Nokia undergo several big convulsions this century. The last happened in 2016, when Nokia bought Alcatel-Lucent in a €15.6 billion ($16.9 billion, at today's exchange rate) deal. Unimaginable as it seems now, operators at the time voiced no objections to the disappearance of another player, according to a European Union document signed off by Margrethe Vestager, the commissioner who remains a bête noire for many telecom executives.

In fact, some telcos were positively enthusiastic about the prospect of more vendor consolidation, wrote Vestager. "[In] their view, the transaction would indeed strengthen Nokia's and Alcatel's respective proposition to customers and guarantee viable competition going forward in the RAN equipment marketplace," she said.

The rationale would seem to be that a handful of muscular players is preferable to a busload of weaklings. It's the same logic telcos use to justify merger plans that would reduce the number of mobile networks in a country from four to three. Economically, those tie-ups make a lot of sense. But you probably won't hear that from many customers.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

_International_Software_Products.jpeg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)