Telcos will applaud Intel's charge at Nvidia as AI hype goes imbecilic

An Nvidia monopoly in AI chips and the connectivity between them alarms some operators, but alternatives may be emerging to satisfy the seemingly rampant demand.

The world's supposedly smartest people are saying some of the dumbest things about artificial intelligence (AI). The latest comes from free-speech champion Elon Musk, who this week predicted the emergence of artificial superintelligence, exceeding the cognitive powers of any man or woman, next year – provided the electricity grid doesn't crash or that melting polar icecaps haven't turned Earth into a giant slushy sooner than climate alarmists expect.

Musk's timeline sounds even scarier than Jensen Huang's. Earlier this month, the Nvidia boss envisaged the arrival of artificial general intelligence (AGI, to abbreviation lovers, as opposed to generative artificial intelligence's GenAI) by 2029. This is the sort of AI you read about in novels or see in movies, where machines are indistinguishable from humans and an even more robotic-than-usual Arnold Schwarzenegger says, "I'll be back," before terminating everyone in a spray of bullets.

What does AGI or superhuman AI even mean? Machines already beat people at the most complicated games. Ever since the dawn of the calculator, they've outperformed us at basic arithmetic. But human intelligence isn't easily quantifiable. The human brain isn't made of silicon chips and wires that Huang's employees can tinker with. It's a mushy grey blob whose inner complexity defies the understanding of the cleverest neuroscientists. Equating a biological specimen – the output of an evolutionary process that took millions of years – with some just-written lines of computer code is fatuous.

Ubiquitous AI

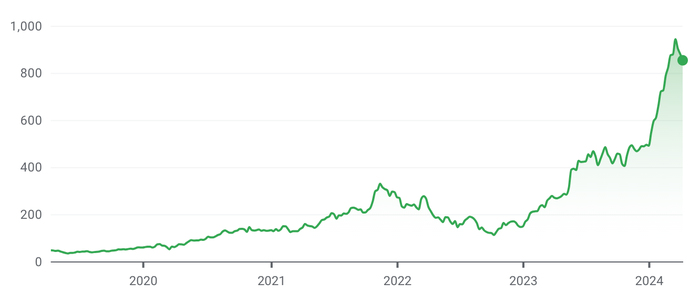

Musk and Huang are doing it, of course, because it garners headlines and drives up the stock. Nvidia, the main beneficiary of the AI revolution, was worth less than $50 per share about five years ago. Today it trades at more than $850 and has a market capitalization of more than $2 trillion. Not bad for a company whose chips, which can essentially perform multiple calculations simultaneously, were originally designed for graphics in games – hence the graphics processing unit (GPU) label. These days, of course, they're AI chips first and foremost. It's a wonder the GPU label has survived. In Musk's case, megalomania is explanation enough for the regular outbursts.

Nvidia's share price ($) on Nasdaq (Source: Google Finance)

Meanwhile, it seems everyone from Microsoft to your local mom-and-pop shop wants to be seen as an AI company. Everything seems to be AI-powered. A few years ago, this reporter wrote about predictive maintenance technology without a single reference to AI. But the same technology now would almost certainly be marketed as predictive AI, even if nothing had changed. Data analytics is AI. All pattern recognition is AI. Anything that involves the part-automated modification of images – such as that infamous photo involving Kate Middleton (aka the Princess of Wales) – is AI. She'd been digitally inserted among her family, it transpired – something magazine people were able to do back when they could smoke in the office.

"AI is here to stay. AI is the future. We now use AI in some 400 projects," said the perennially excitable Deutsche Telekom boss Timotheus Höttges in a statement today. He would love his company's share price to have done an Nvidia. Alas, the German operator is up from just €15 a share five years ago to about €22.50 this week, having at least outperformed its telco peers across Europe.

Others clearly believe something must be done about Nvidia. "This is a very weird moment in time where power is very expensive, natural resources are scarce and GPUs are extremely expensive," said Bruno Zerbib, Orange's newish chief technology officer, during an interview with Light Reading at this year's Mobile World Congress (MWC). "You have to be very careful with your investment because you might buy a GPU product from a famous company right now that has a monopolistic position."

Intel's holy family of chips

He will, then, presumably welcome the latest update from Intel, a chipmaker that seems to be losing its religion. Intel still makes just about all its money from central processing units (CPUs), based on its x86 architecture, lodged in personal computers and servers. These "general-purpose" chips are, as that moniker implies, extremely versatile. But, like any generalist, they do not excel at specific tasks, including numerous applications lumped together under the AI umbrella. Hence an Intel lurch to what it calls "accelerators." And the latest, Gaudi 3, takes direct aim at Nvidia.

The competitor is mentioned no fewer than six times in Intel's main press release about Gaudi 3. That chip, it claims, is 40% more energy efficient than Nvidia's best-selling H100 GPU and available at a fraction of the cost. Given certain parameters, it takes half as long to train Gaudi 3 on Llama2, an open-source large language model (the gubbins behind applications such as ChatGPT). And unlike Nvidia, Intel is trying to build an "open" software platform for Gaudi 3, involving lots of other companies and commonly used tools. CUDA, the software that underpins Nvidia's GPUs, has been criticized for being proprietorial.

Intel is also positioning Ethernet as the connectivity glue for these AI accelerators. Nvidia's preference is a technology called Infiniband, which it inherited with its $7 billion takeover of Mellanox in 2020. This bothers people worried about Nvidia's monopoly because Nvidia through Mellanox is effectively the only vendor of Infiniband technology. It's a worry for technological reasons, too.

"The way it operates right now is you have to have these really large cluster farms of Nvidia GPUs, and the reason they are collocated is they're using really low-latency Infiniband connecting them together – between the compute platforms," said Howard Watson, BT's chief security and networks officer, when he met Light Reading at MWC (video here).

"What I would really want to see is at some point that shifting to Ethernet, so therefore you can start to distribute those GPUs into more and more locations," Watson continued. "My vision is ultimately we could host small GPU clusters in the network. You could use them for the training phase of generative AI and then – in the inference phase – lots of opportunities in how we distribute the compute across the network."

Tensor strength

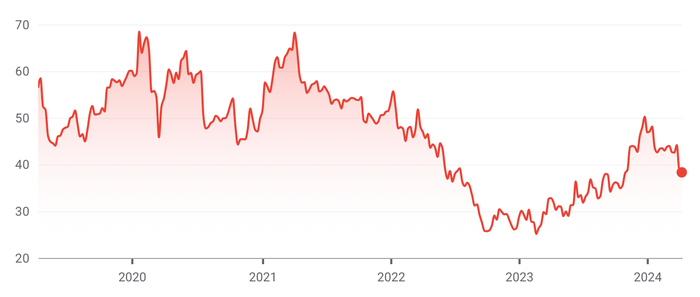

Whether Intel's claims stack up will be known after these chips go on sale later this year. But Gaudi 2, Intel's current-generation AI chip, did little to boost Intel's fortunes last year, when sales at its data center and AI unit dropped nearly $4 billion, to $15.5 billion, and it suffered a $500 million operating loss, compared with a $1.3 billion profit in 2022.

This was blamed partly on a slump in CPU spending by hyperscalers, which shifted a lot of that spending to Nvidia instead. In stark contrast to Intel, Nvidia reported a 126% increase in revenues, to about $60.9 billion, for the fiscal year to end-January 2024, and pocketed $29.8 billion in net profit, a 581% increase. The notable absence of GPU competition was evident in its gross margin – up 15.8 percentage points, to 72.7%.

Intel's share price ($) on Nasdaq (Source: Google Finance)

A danger for Intel is that Gaudi 3 cannibalizes CPU sales, although Intel would probably settle for that if its financial profile looked comparable to Nvidia's. Elsewhere, though, such as the radio access network market, it seems desperate to present its accelerators as a mere CPU supplement or "boost," and not as proof of heavier customization.

The AI problem for Intel is that numerous other companies are also going after Nvidia. And the biggest challenge to Huang's business probably comes from its biggest customers and their in-house silicon investments. Google's tensor processing units (TPUs), for instance, could feasibly substitute for Nvidia's GPUs in some cases. Nvidia's share price is down 9.5% from a lofty $942.89 on March 22. But as Musk and Huang spout off about machines with human attributes, further growth would surprise no one.

Read more about:

AIAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)