GenAI threat to white-collar workers highlighted by IMF

Previous rounds of automation mainly affected lower-skilled employees, but this one is likely to be different.

There's a darkly amusing scene at the start of Saltburn, which was nominated for several Golden Globes this year, when a math nerd desperate to show off his arithmetical skills, fuming at the main character's reluctance to quiz him, bellows "just fucking ask me a sum, then" in a crowded Oxford University dining hall. At one time, such human abaci would have been in demand for "medium- to high-skill jobs," according to a new report from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). But the arrival of the electronic calculator made them far less valuable. They are today a striking example of the impact technology can have on white-collar roles.

Just as many former jobs in accountancy have vanished, so other "cognitive" occupations could now be decimated by generative artificial intelligence (AI) of the ChatGPT variety. It's a standout finding of the IMF report, which explores the ramifications of genAI for "the future of work," as the authors put it. Previous technological upheavals mainly affected less skilled roles, driving successive waves of people into jobs that put a premium on brainpower. With genAI, even the most highly skilled workers "face potential disruption," says the report.

This is extremely pertinent for a telecom industry full of bright sparks that has been shrinking for years. Long before genAI was a thing, the telecom industry had been in heavy denial about the impact automation would have on its workforce. Technology might kill some jobs, conceded executives and press relations staff in the late 2010s. But its main effect would be to liberate employees from workplace drudgery and allow them to fill their days with more interesting tasks, they insisted. The Industrial Revolution had put handloom weavers out of business but created thousands of new jobs. There was no reason to think automation and AI in telecom would be any different.

Amid continued layoffs, that is certainly not the prevailing message now. Philip Jansen, who quits the CEO role at BT this month, last year reckoned AI would claim about 10,000 of 130,000 jobs at the UK telco by 2030. Another 45,000 will have disappeared for other reasons, he expects. Senior technology executives increasingly talk up fully automated, "zero-touch" networks unsullied by humans. Software can plan networks, maintain them and adapt them rapidly to changing conditions. With genAI tools, it can even write itself.

The ongoing need for humans

Of course, not all telco-sector jobs will disappear. Most of the decision-making (for now) will still be left to people. Rather than seeing genAI as an outright substitute for customer-service and other jobs, most telcos view it as a necessary complement, a tool to boost the efficiency of remaining staff. The IMF report strikes a more upbeat note when it says that about 30% of jobs in developed markets "could benefit from enhanced productivity through AI integration." Those productivity gains "could result in higher growth and higher incomes for most workers," it says.

Entrusting the network to machines and a handful of boardroom staff would be as mad as undergoing remote-control surgery over 5G in a hospital with a weak signal. Its proven fallibility and habit of inventing stuff shows genAI is far from perfect. It is certainly not intelligent in a human sense, and it might never be. If it were, people should arguably be even warier of full automation. Putting a sentient, self-interested AI in control would be like ceding power to an alien race.

A more immediate risk is of the telecom industry, and wider society, losing foundational expertise. Schools obsessed with mental-arithmetic tests face the accusation they are teaching obsolete skills. That all sounds reasonable until the technology breaks at a critical moment. The telco rush to automate boring but skilled tasks could ultimately leave companies without employees who understand the basic plumbing. In the absence of wholly trustworthy AI, that is a worry.

Telcos under pressure

Nevertheless, enthusiasm for automation is rife, and it is not surprising. Telcos have largely failed to unearth any new growth opportunities beyond smartphone, home and office connectivity. Services have been commoditized and prices have been driven down by competition. But the cost of building and maintaining networks remains high. Automation may be the best route to juicier profits and happier shareholders.

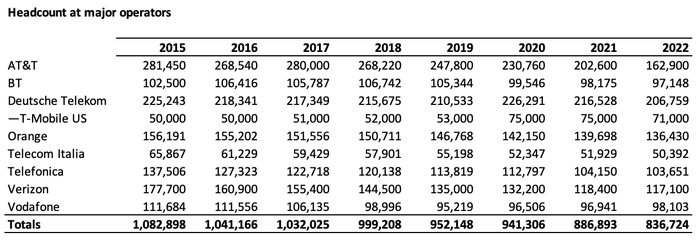

The western world's largest telcos are certainly united by their efforts to reduce headcount. Since 2015, the eight most prominent telco brands in Europe and North America (AT&T, BT, Deutsche Telekom with its T-Mobile US subsidiary, Orange, Telecom Italia, Telefónica, Verizon and Vodafone) have collectively cut their combined headcount by more than 285,000 jobs, a figure equal to about one fifth of the 2015 total.

(Source: companies, Light Reading)

Numerous factors have been at play, including mergers and acquisitions, the disposal of non-core assets, a more rigorous enforcement of the usual efficiency measures and – of course – the diminution of various business activities. But automation has contributed. For customers seeking help, chatbots are increasingly the default. Software has replaced many of the people who once ran network operations centers. One former technology executive at a major telco recently said there was no part of the network unsusceptible to automation.

GenAI was widely seen as one of the big trends in telecom (besides other sectors) last year. Yet the technology had barely then emerged from the labs of OpenAI and other developers. Not even the most receptive telcos have had much opportunity to unleash ChatGPT and similar applications outside a test environment. And concerns have still not been addressed. But 2024 seems likely to feature deployments by more adventurous telcos in a variety of commercial scenarios, with potentially far-reaching consequences for employees. Depending on how fast the industry moves, many could end up feeling like the math nerd in Saltburn – undervalued, and desperate to be used.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

_International_Software_Products.jpeg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)