Intel losses raise concern about the future of cloud RAN

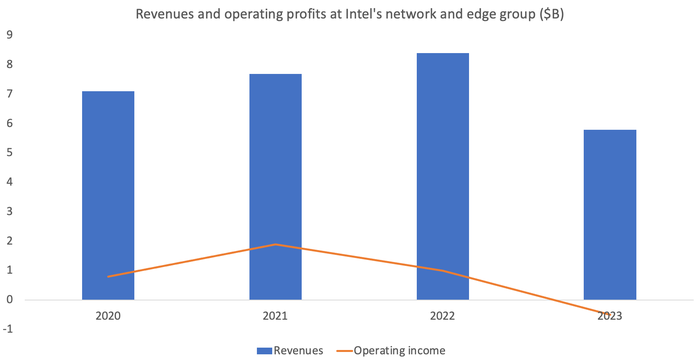

Intel's network and edge group swung from a $1 billion operating profit in 2022 to a $500 million loss last year as sales plummeted.

One of the few other suppliers named when Ericsson landed its $14 billion radio access network (RAN) contract with AT&T last month was Intel. The US chipmaker has a close relationship with the Swedish manufacturer of mobile networks and is set to churn out purpose-built 5G chips for Ericsson based on 2-nanometer designs in future. Yet the Xeon processors Intel develops for cloud RAN will not feature in the initial rollout, and the word on the street is that AT&T will not introduce them until 2026. In the meantime, Intel's still-young network and edge group looks badly winded.

Hurt by a spending slowdown, it swung from an operating profit of $1 billion in 2022 to a loss of $500 million last year, Intel's latest filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) shows. After growing its sales from $7.7 billion in 2021 to $8.4 billion in 2022, it also recorded a massive $2.6 billion slump in revenues last year, to $5.8 billion.

This 31% plunge in revenues is obviously much steeper than the 15% sales decline Ericsson reported at its networks business for 2023 on a constant-currency basis, or the 5% drop at Nokia's equivalent unit. Intel's SEC filing identifies both Nordic vendors in its list of customers for network and edge products, along with Cisco, Dell, HPE, Lenovo, Amazon, Google and Microsoft. Many seem to have cut spending after an earlier build-up of inventories. Even where stocks have been depleted, network operators facing sluggish growth have resisted pressure to upgrade.

(Source: Intel)

Tortoise speed

Cloud RAN, moreover, is advancing at tortoise speed, as evidenced by AT&T's prioritization of purpose-built Ericsson kit over the rollout of general-purpose hardware. When he crunched the numbers last year, Joe Madden, the founder and lead analyst of Mobile Experts, estimated that virtual RAN (or vRAN) products generated just $100,000 of Intel's revenues for 2022.

Slow progress explains why Intel missed its 40% market-share target in the market for basestation silicon that year, managing 31%, according to Madden's estimates. "Their goal of capturing 40% assumes that vRAN will take off quickly and that has not happened," he previously told Light Reading by email. Competition to Intel in this market is also emerging this year, driven by the industry's desire to avoid an Intel monopoly.

Some prominent telcos are still not sold on the concept years after it was first aired. "I have said to vendors we are not doing cloud RAN unless we get multitenancy benefits and scaling," said Mark Henry, BT's director of network and spectrum strategy, during an interview with Light Reading in November. "If it is just putting baseband in a building, we've already paid for infrastructure and cabinets and still have to upgrade the infrastructure and cabinets to do it."

The dire revenue performance and hefty loss at this network and edge unit has got some industry figures talking about Intel's commitment to cloud RAN. There are, to mutilate an English proverb, much bigger chips to fry, and analysts on its recent earnings call were far more interested to know about Intel's role in artificial intelligence (AI), where the challenge from Nvidia is a greater worry than anything to do with the RAN. Network and edge products last year accounted for just 11% of Intel's revenues, which dropped 14%, to $54.2 billion, after a $5.7 billion decline in sales of PC, data center and AI chips.

Like many other technology companies, Intel is currently in cost-saving mode and cut its headcount by 7,100 employees last year, to 124,800 at the end of December. But any cuts to the cloud RAN business could upset the whole ecosystem given Intel's outsized role in the market. Around this time last year, Intel claimed a 99% share of all virtual RAN deployments. RAN developers such as Altiostar (now owned by Japan's Rakuten), Mavenir and Parallel Wireless even built their software initially on Intel's FlexRAN reference design.

Industry split

Meanwhile, bickering over the method of RAN cloudification has split the industry and undoubtedly caused delays while operators weigh their approach. The main disagreement, essentially, is over how much of the RAN software should be handled by a general-purpose processor (GPP). Intel – unsurprisingly, as the world's biggest vendor of GPPs – backs an approach sometimes referred to as "lookaside" where the GPP supports all but one or two resource-hungry functions. But others reckon the entire Layer 1, the most demanding category of functions, needs offloading onto separate, purpose-built chips known in this context as inline accelerators.

Intel's seemingly valid rejection of inline is that it essentially excludes Layer 1 from the cloud. Software is "hard coded" for these purpose-built chips and not reusable on other silicon. Resources cannot easily be shared, as they can with commonly used hardware and software platforms. Yet outside telecom there is a broader shift away from GPPs and toward "accelerated computing" for specific applications, such as the graphical processing units Nvidia pitches for AI. Inline is merely reflective of this trend, say its backers.

Nor are the lookaside and inline camps as far apart as some make out (indeed, those labels are becoming outdated). In more advanced 5G networks, Intel recognizes the need for hardware accelerators that are not programmable to support both forward error correction (FEC) and some channel-estimation processing. Ericsson, which publicly backs Intel's approach, has previously downplayed the FEC as a point of competitive differentiation between software vendors. But channel estimation is perhaps more important.

If critics are right to argue that Intel's cloud RAN chips are becoming more purpose-built, the main considerations for telcos lie elsewhere. Granite Rapids D, a forthcoming range of Intel chips aimed specifically at cloud RAN, combines numerous components in a customized server, including hardware acceleration for the FEC, fast Fourier transform (FFT) and sounding reference signal (SRS) functions, according to a source with knowledge of the matter. It also bundles in a 400Gbit/s Ethernet controller for the fronthaul connection, along with mobile ciphers for encryption, said that source.

The upshot may be something that no longer fits the description of "common, off-the-shelf" server. And because it aggregates so many features, a telco would have to invest in a whole new server even if it wanted only to add some Layer 1 capacity. This could be a key advantage of putting Layer 1 inline accelerators on separate cards. With Layer 1 disaggregated in this way, an operator could, in theory, use them with a variety of servers. That includes equipment from new Intel competitors basing their GPPs on the blueprints of Arm, a UK-headquartered chip designer. Granite Rapids D, by contrast, seems to encourage Intel "lock-in."

Nevertheless, unless it makes a U-turn AT&T is likely to be a prominent customer of Granite Rapids D, considering the roadmap it has chosen. Verizon in the US has also publicly championed Intel's approach over the use of accelerator cards. In a white paper it co-authored with Ericsson in 2022, the operator derides these cards as energy hogs. It also says the need for proprietary software to go with their underlying chips "eliminates the possibility to create a common cloud compute infrastructure across the network and increases the risk of fragmentation."

What's hard to imagine is much cloud RAN growth this year. Dell'Oro, a market research firm, expects overall RAN market sales to shrink from about $40 billion in 2022 to $35 billion this year. Omdia, a Light Reading sister company, is also guiding for a contraction, albeit at a lower rate than it saw last year. Shareholders in big chipmakers may be wondering why they should bother.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like