Spectrum has never been so cheap – not in the UK, anyway. Back in 2000, UK operators were fleeced by government authorities for £22.5 billion (US$31.3 billion) during an auction of licenses for 3G, an underwhelming technology now being phased out. Thirteen years later they forked out another £2.3 billion ($3.2 billion) for 4G, an impressive successor. By the time 5G rolled along, in 2018, the fee had dropped to just £1.4 billion ($2 billion). The depression lasts. Wrapping up today, this week's follow-on sale raised the same amount. Hang around till 6G and spectrum might even be free.

That is probably a forlorn hope while Europe's governments, the UK's included, continue to treat their telecom operators as cash-filled piñatas to be whacked at regular intervals. Never mind that £1.4 billion equals just 0.07% of the UK's borrowings. Or that national debt is growing by £1 billion ($1.4 billion) a day to pay for a lockdown that is starting to look far more harmful than the virus it is meant to contain, already neutered in the old and vulnerable through vaccinations. To four companies that have not entirely escaped the economic squeeze – facing higher taxes and shelling out hundreds of millions to replace Huawei, a Chinese supplier the government has banned – it is a further pinch.

Figure 1:  The government approach to service providers.

The government approach to service providers.

A couple of them had asked for the auction to be scrapped in the circumstances and replaced by a simple administrative charge for new 5G licenses. Ofcom, the regulator, was having none of it. Demand is too great, said CEO Melanie Dawes, "from your companies and potentially others." Guess what? The only companies that showed up were the four that already operate networks. And demand was so great that spectrum went for less than it ever has.

Dwindling value

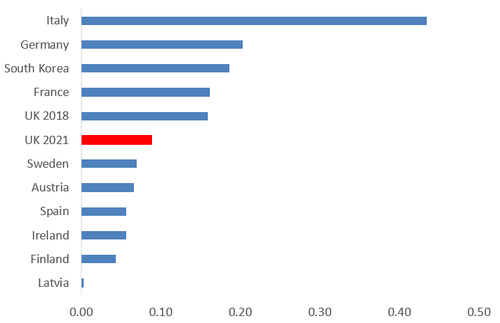

The difference was stark in the mid-band, the collection of airwaves between 3.4GHz and 3.8GHz that are most closely associated with 5G. Two years BC (before coronavirus), operators paid $0.16 for each MHz they received divided by the population (a measure called per MHz pop in the industry). This time round, they spent just $0.09. In total, those licenses went for £512.4 million ($712 million). The other £844 million ($1.2 billion) was spent on 700MHz spectrum – good for coverage, bad for anything vaguely 5G-ish.

The diminishing value of spectrum probably reflects the economic malaise, to some extent. Since 2018, operators have also been able to step back and survey the partly built 5G property that was at the planning stage three years ago. It is still far from being the grand design they would have imagined.

But auction mechanics explain why operators paid less, too. Unlike in 2018, no operator actually needed mid-band spectrum to be able to launch a 5G service. And Three chose to sit out the mid-band sale entirely, having amassed enough spectrum to power several 5G networks thanks largely to its £250 million ($347 million) takeover of UK Broadband a few years ago. Its absence tilted the supply-demand seesaw favorably for operators.

Band | Operator | Amount (MHz) | Price ( GB pound ) | Price per MHz pop ($) |

700MHz | EE | 40 | 284,000,000 | 0.15 |

700MHz | Hutchison 3G UK | 20 | 280,000,000 | 0.29 |

700MHz | Telefonica UK | 20 | 280,000,000 | 0.29 |

700MHz | − | 80 | 844,000,000 | 0.22 |

3.6-3.8GHz | EE | 40 | 168,000,000 | 0.09 |

3.6-3.8GHz | Telefonica UK | 40 | 168,000,000 | 0.09 |

3.6-3.8GHz | Vodafone | 40 | 176,400,000 | 0.09 |

3.6-3.8GHz | − | 120 | 512,400,000 | 0.09 |

Source: Ofcom. |

Nevertheless, that BT, O2 and Vodafone each paid about the same fee for the same 40MHz amount proves the whole set-up is a farce. To bill it as an "auction," with its connotations of a competitive process that could throw up surprise winners, is to mislead the wider world. An auction run like one at Sotheby's – where some shady billionaire slopes off with a national treasure – would, of course, suit hardly anyone. For the sake of competition, Ofcom wants an even distribution of spectrum, as do wise consumers. Sotheby's probably loves it when prices clearly exceed value. Ofcom never should, even if it presided over that kind of outcome in 2000.

It was a similar story in the 700MHz band, where BT, O2 and Three each bought a 20MHz license for about £280 million ($389 million). BT topped that up with another 20MHz of downlink spectrum for just £4 million ($5.7 million, raising questions about its usefulness), while Vodafone sat this one out. It plans instead to refarm its 900MHz airwaves for 5G, says Paolo Pescatore, an analyst with PP Foresight.

Want to know more about 5G? Check out our dedicated 5G content channel here on Light Reading.

Defenders of the process may note that Ofcom raised only about £300 million ($417 million) more than its starting fee. The administrative process championed by Vodafone and Three might not have saved them anything material. But that is surely not the point if it would have removed risk and been easier for the operators. What's more, other European countries have collected even lower fees on a per-MHz-pop basis. China basically hands it to operators for free.

Figure 2: Price per MHz Pop ($) for 3.4-3.8GHz spectrum  Source: Companies, regulators, Light Reading.

Source: Companies, regulators, Light Reading.

Ofcom could do this while still holding operators to account through stringent coverage obligations. The penalties European regulators have dished out for missing these are usually pathetic. That need not be the case, though. A fine comparable to an auction settlement would probably concentrate telco minds. Dropping the upfront charge would also leave money in the pocket for network rollout. If 5G is so important to economic prosperity, as the government keeps insisting, then everyone's a winner.

Few complaints, for now

No one is grumbling in today's aftermath, though. This auction went as smoothly as the UK's COVID-19 vaccination program, providing a much-needed spectrum injection for all its participants. "Winning prized 700MHz spectrum was particularly important to EE and Three," said Kester Mann, an analyst with CCS Insight, in an email. "Both were lagging in low-band frequencies, which are best-suited to achieving wide-area, rural and in-building coverage." O2 scooped important low-band and mid-band airwaves, he said, while Three can remain satisfied with its total haul.

In a contrast to earlier days, when a spectrum imbalance, and Ofcom's questionable decision to give a 4G head start to EE (now part of BT), led to years of fighting, peace reigns throughout 5G-land. "We are delighted with the result, which secured the right spectrum at a fair price," said O2 boss Mark Evans. His rivals were similarly upbeat. After a year that has seen dividend scrappage, declining sales and government intrusion into the supplier landscape, executives have something to smile about.

Allocation | Amount | Operator |

3410-3460 | 50MHz | Vodafone |

3460-3500 | 40MHz | Three |

3500-3540 | 40MHz | O2 |

3540-3580 | 40MHz | BT |

3580-3680 | 100MHz | Three |

3925-4009 | 84MHz | Three |

Source: Ofcom. |

And yet, the 5G spectrum saga is far from done. An insistence on the auction process is arguably not Ofcom's worst regulatory failing. To get the most out of 5G, operators need large contiguous spectrum blocks, not something as gappy as an eight-year-old's grin. By running two auctions three years apart, Ofcom has created a situation in which operator mid-band holdings are broken across two separate ranges. The only operator with more than 40MHz of contiguous spectrum is Three, a fact it previously advertised as "real 5G" before it was silenced by UK watchdogs.

Ofcom generosity means operators will be allowed to meet furtively to sort out this mess. It could mean O2 exchanging the spectrum it has just won for the airwaves BT received in 2018, for instance – a swap that would leave O2 with 80MHz of contiguous 5G spectrum but whose implications for BT remain unclear. Finding a solution that favors all operators could be like Rubik's cube by committee, driving anyone to alcoholism. When pubs finally re-open, they may feature some frazzled-looking men slurping pints over frequency charts.

Related posts:

— Iain Morris, International Editor, Light Reading

Read more about:

EuropeAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like