Huawei amid sanctions beats Ericsson and Nokia on every measure

The Chinese equipment vendor seems to have had a much better year than either of its Nordic rivals and now dwarfs them on R&D spend.

Huawei's default settings look like melodrama for the bad times and humility for the good. When it was first struck by US sanctions, the Chinese equipment maker compared itself to a fighter plane hit by flak whose sole mission was to remain airborne. After gaining significant altitude last year for the first time since 2019, it showed restraint rather than jubilation. "We've been through a lot over the past few years. But through one challenge after another, we've managed to grow," said Hu Houkun, the rotating chairman who currently sits in the pilot's seat, in its latest annual report.

If US sanctions were intended to put Huawei in a fatal tailspin, they have clearly missed their target. Yes, the company's sales last year were 21% down on the high point of 2020. But that is due entirely to a collapse at Huawei's smartphone business and not to any engine problems in networks, the unit that supposedly had US authorities in such a panic. Their justification for cutting Huawei off from vital US technologies (not, seemingly, as vital as everyone thought) was that dastardly Chinese forces might slip something nasty into Huawei's network products, then popular among US allies.

Strikingly, this networks unit – today called the "ICT infrastructure" business – last year outperformed both Ericsson and Nokia, Nordic rivals allowed to cruise freely through airspace in Europe and other countries that Huawei had previously occupied. Its headline revenues were up 2.3%, to about 362 billion Chinese yuan (US$50 billion). On a constant-currency basis, Nokia's (generated almost entirely from network sales) fell 8% while revenues at Ericson's mobile networks unit dropped 15%.

The China syndrome

Both European companies were badly hurt by spending cuts in the US, from which Huawei has been largely excluded for years. And while Huawei has lost a few deals in Europe and other pro-US countries, American lawmakers can do little about its position in China, home to about 1.4 billion people and gazillions of mobile sites. Indeed, that position looks even stronger. An unwelcome consequence of the European backlash against Chinese vendors seemed to be the loss by Ericsson and Nokia of market share in a retaliatory China. At Ericsson, which breaks out the figure, China sales dropped from 15.9 billion Swedish kronor ($1.5 billion) in 2019 to SEK10.7 billion ($1 billion) last year.

Operators still buying network products from Huawei do not appear to have seen the drop-off in performance that someone buying a Huawei smartphone amid sanctions would have experienced. This is partly because Huawei has always designed its own network software, while its smartphones previously used the Android operating system that originated with Google. On the networks side, it also looks more self-sufficient in hardware.

What it currently lacks is access to Samsung and TSMC, the world's most advanced chip foundries, both furnished with US tools. Networks, however, are typically a couple of generations behind smartphones on the size of transistors. Forthcoming iPhones will reportedly feature chips based on the 2-nanometer (billionths of a meter) process. The Nokia basestations that include 5-nanometer chips are considered cutting edge.

If Huawei now looks worse off here, it continues to boast other advantages. Those include the design of power amplifiers based on gallium nitride, seen as a more energy-efficient option than silicon. "For this component, we are leading the industry one generation ahead of our competitors, and that is why, according to third parties who report, we keep leading market share," said Philip Song, the chief marketing officer for carrier networks, during a press conference at the recent Mobile World Congress in Barcelona.

The seeds of growth

However its products measure up against those of Ericsson and Nokia, Chinese operators clearly source a bigger share of their equipment from Huawei and local rival ZTE than they ever have. As 5G matures, and questions surround the telco investment case for a future splurge on even more advanced equipment, Huawei faces many of the same business-model challenges as its western rivals. But unlike those companies, it has several growth stories to tell.

These include a consumer unit in apparent recovery. Huawei seems to have obtained 7-nanometer chips from SMIC, a Chinese foundry, and used these along with in-house 5G designs and operating-system software to produce a smartphone branded the Mate 60 Pro, confounding critics who assumed US sanctions had put such technologies beyond reach. Demand for that gadget helped to boost consumer revenues by 17%, to about RMB251 billion ($34.7 billion).

This is still far below the RMB483 billion ($66.8 billion) it reported in 2020, before Huawei sold off some of its smartphone assets. And critics doubt SMIC can profitably crank out large volumes of 7-nanometer chips without access to extreme ultraviolet lithography machines. The supply of those is currently monopolized by ASML, a Dutch company. And Dutch authorities have denied ASML export licenses to serve China.

Much smaller, but potentially important, are Huawei's cloud computing, digital power and intelligent automotive solutions units. The first, in particular, could ultimately play a big role in China, where the main rival is Alibaba, another local firm, and not AWS, Google or Microsoft, the "hyperscalers" that have put down roots elsewhere. International concern about the power of those three US companies could be an opportunity for Huawei in some countries, according to Huawei employees. Sales rose 22% last year, to more than RMB55 billion ($7.6 billion).

An R&D chasm

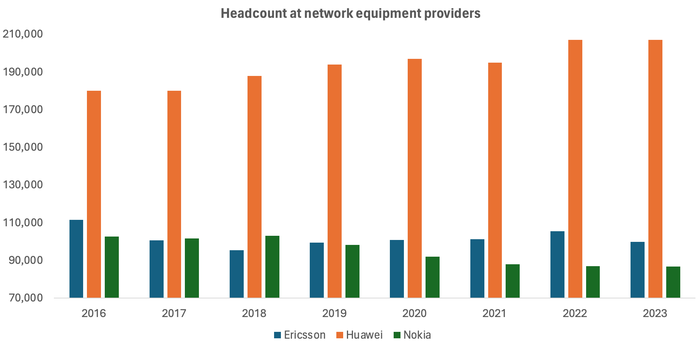

But the big difference between Huawei and its European rivals is at the resources level. A US spending slowdown has resulted in further shrinkage at Ericsson and Nokia, which together cut nearly 5,800 jobs last year and today employ about 27,500 fewer people than they did in 2016. Huawei, by contrast, made no changes last year and has gained 27,000 employees since 2016. What's more, at current exchange rates, Huawei makes dramatically more in sales per employee than either Ericsson or Nokia. Its figure of about $472,000 last year compares with roughly $276,000 at Nokia and $245,000 at Ericsson.

(Source: companies)

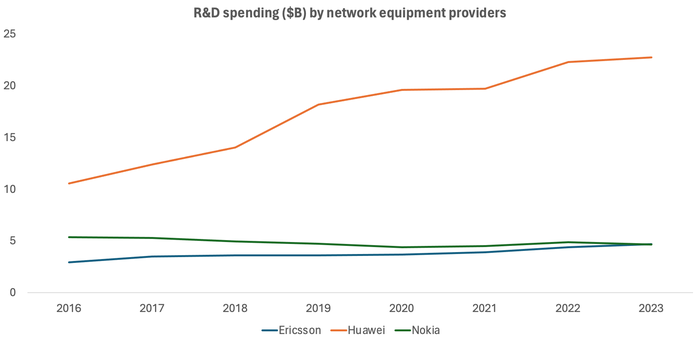

A chasm has opened in research and development (R&D). In 2016, a Huawei already generating more than a third of its revenues from consumer gadget sales outspent a combined Ericsson and Nokia by less than $2.3 billion, at today's exchange rates. Last year's difference was $13.4 billion. Ericsson has upped annual spending by around $1.8 billion over this period, while Nokia has cut it by $720 million. Huawei's annual investments have grown by $12.2 billion.

(Source: companies)

Critics insist a direct comparison is invalid because Huawei is active in sectors the Nordic vendors have either quit or never entered. As reasonable as that sounds, the gap would be significant even if R&D spending reflected the split of sales. Last year, for instance, some 51.4% of Huawei's revenues were generated at its ICT infrastructure unit. The same percentage of R&D expenditure equates to about $11.7 billion.

The US may be running out of ammunition. Its main weapon was always the west's dominance of the semiconductor industry. That came via companies like Intel, Qualcomm and Nvidia – the designers of chips – as well as the software and tools used in mainly Asian foundries. But the Biden administration has done about as much as it can to close loopholes and seal off Chinese access. As China works hard to develop homegrown alternatives, it is the west's own equipment vendors that are struggling.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)