Ericsson slashes 5G outlook by 400M subscribers

Ericsson blames delays to spectrum auctions in several countries and macroeconomic difficulties for the sharp revision to its forecast.

Fifth-generation (5G) mobile is not going to plan – or not the way Ericsson planned it. Every few months, the Swedish equipment maker publishes a "mobility report," documenting the progress of cellular technology. It is always full of garish graphics, big numbers and discourse on the exabyte explosion triggered by smartphone use. Charts usually feature lines that slope up like San Franciscan streets or bars that rise like steps. But in the latest edition, published this week, they are not climbing as fast as Ericsson previously expected.

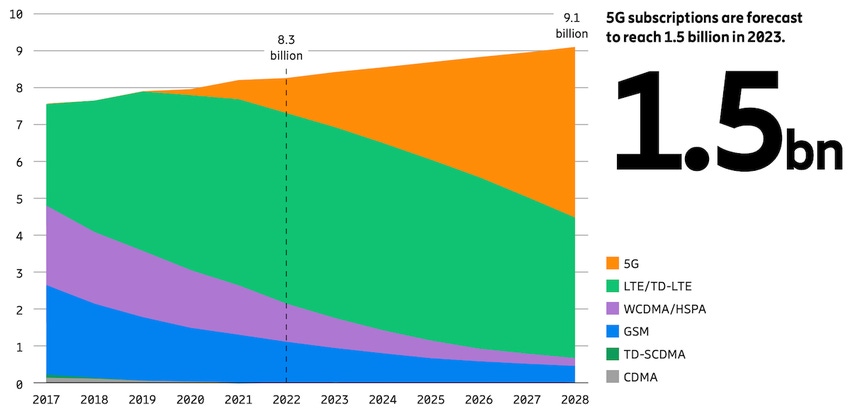

Back in November, Ericsson predicted there would be 5 billion 5G subscriptions in the world by the end of 2028, as operators took advantage of new spectrum licenses and built out their networks. This would mean 5G accounting for about 55% of all mobile subscriptions that year. By June, however, Ericsson had made a rather dramatic downward revision. The forecast of 5 billion subscriptions had been lowered by a whopping 400 million, or 8%, to 4.6 billion instead. Putting a dent of 100 million subscribers in Ericsson's forecast of total mobile subscriptions, this change cuts 5G's share of that total to about 50.5%.

Mobile subscriptions by technology (billions)

The massive cut was easy to miss. Ericsson led its report with a headline about 5G mobile subscriptions reaching 1.5 billion this year, burying details about 2028 in the small print. Nor did it refer to its November report and specify the precise change it had made since then, merely saying its forecast had been "adjusted" because of some unforeseen developments. The main culprits appear to be delays to spectrum auctions in several countries – a perennial bugbear for Ericsson – and macroeconomic nastiness.

This is all rather alarming for Ericsson. Although it is branching into software and pitching its wares at carmakers, factory owners and other companies that have never previously bought network products, it still generates most of its income by selling 5G equipment to operators. If those operators aren't building networks because they can't afford it or don't have the spectrum, Ericsson isn't making money.

Overexposed

Its exposure to this market is shown whenever it publishes financial results. For the first quarter of this year, for instance, it hauled in about 62.6 billion Swedish kronor ($5.4 billion) in total revenues, 68% of which it generated at its telco networks unit. More importantly, networks is the only one of Ericsson's four units that makes any operating profit. That shrank 21% for the first quarter, to SEK6 billion ($510 million), compared with the same period of 2022. But without it, Ericsson would have recorded a SEK2.9 billion ($250 million) loss.

Investors took fright on April 18 when Börje Ekholm, Ericsson's CEO, said the outlook this year was "choppy" and spoke of "poor visibility" in the market. By the end of the day, Ericsson's share price in Stockholm had fallen 8.6%. Big customers in North America are in a belt-tightening mood after an earlier binge on 5G equipment. Were it not for India, whose operators are currently racing to deploy 5G, Ericsson's results would have been much worse. Sales fell year on year in every one of Ericsson's geographical "market areas" apart from "South East Asia, Oceania and India."

A 400 million difference in subscriber numbers might affect Ericsson's customers more than it hurts Ericsson. One scenario is that cash-strapped consumers refuse to upgrade to the 5G networks operators have built. Something like that could be blamed on the "difficult macroeconomic conditions" Ericsson refers to in its latest mobility report.

But operators in many countries don't even attempt a 5G upsell – they simply provide it to subscribers with compatible gadgets at the same low rates previously charged for older network services. A likelier explanation for the missing 400 million is that 5G networks don't exist. And auction delays – the other reason Ericsson gives for its adjustment – would obviously hinder their rollout, directly harming Ericsson. This is why the Swedish company routinely complains about authorities that take ages to release spectrum to the telecom sector.

Ericsson's downgrade implies there will be 73 million fewer 5G subscribers each year over the forecast period than it previously expected, a figure that represents nearly 7% of subscriber numbers at the end of March. To put it in another context, it is roughly equal to the sum of customers served by all four mobile networks in France.

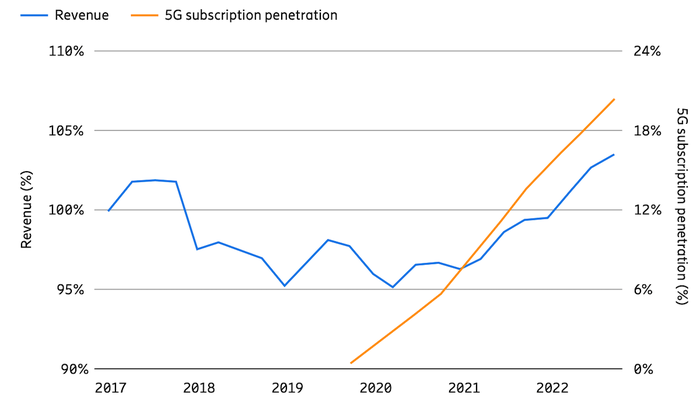

Revenue versus 5G subscription penetration - top 20 5G markets (Source: Ericsson)

(Source: Ericsson)

A big concern for Ericsson right now is some of the negative publicity surrounding 5G. It is frequently made out to be a disappointment that has brought no obvious benefits for consumers while driving up capital expenditure for telcos. To counter that, Ericsson is now trying to convince operators that 5G has already fueled sales growth.

But its case is relatively weak. In countries ranked as the "top 20 5G markets," where average smartphone penetration has risen to about 20% since 2020, telco revenues today are only about 4% higher than they were in 2017, a chart included in Ericsson's latest mobility report appears to show. Desperate times.

Related posts:

— Iain Morris, International Editor, Light Reading

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like