The managed decline of Vodafone

Vodafone's share price is at the same level it was in the late nineties as it continues its retreat from country operations and infrastructure ownership.

In the mid-nineties, when British society was still adapting to the mobile phone, the mere display of a handset in public was seen as vulgar, like revving an Audi's engine at the lights. At the time, they looked like inch-thick, old-fashioned calculators and were good for only voice calls and the exchange of short text messages. But speaking on them in the company of others was a classic faux pas. Between 2000 and 2003, comedian Dom Joly lampooned the worst offenders in his Trigger Happy TV show. "I'm on the phone," he would scream into a three-feet-long replica while sitting in a library or quiet café.

By then, social etiquette had evolved and the gadgetry was becoming widespread. On the London Stock Exchange, Vodafone's share price donned its climbing boots and hiked from a base camp of less than 70 pence sterling in June 1997 to a summit of 528.20 in March 2000. In its 1999 annual report, Ian MacLaurin, then chairman, expressed "delight" at sales growth of 36%, to £3.36 billion (US$4.3 billion, at today's exchange rate), and the addition of 4.6 million new customers, giving it 10.4 million altogether.

Little would he have known at the time that Vodafone had nearly peaked. Just a few months after publishing that report, Vodafone grossly overpaid (as did every other European license winner) for a UK 3G concession with a £6 billion ($7.6 billion) outlay. By September 2002, when Dom Joly was still shouting into his giant phone, its share price had plummeted to just 97.11 pence sterling. Over the subsequent 21 years of cresting 100% penetration (a measure of phones to people) in the age of the mobile Internet, it has never exceeded 300 pence sterling. Today, it trades at just 66.10.

Vodafone's share price (pence sterling) on London Stock Exchange. (Source: Google Finance)

Despite this, Vodafone has become a giant company since MacLaurin was chortling about his catch like a fisherman in well-stocked waters. For the fiscal year ending in March 2023, it reported sales of €45.7 billion ($49.6 billion) and basic earnings of €14.7 billion ($16 billion). It served around 65 million customers on mobile contracts in Europe, also catering to nearly 25 million broadband subscribers, and had 190 million mobile customers across Africa. On this basis, it remains one of Europe's biggest and most important companies. If its infrastructure were ripped away like a scab, the economic damage would be huge.

From Vodafone Idea to no-idea Vodafone

Yet its recent dismal stock-market performance reflects Vodafone's lack of any growth plan whatsoever. It has long since put a phone into everyone's pocket but failed to expand its share of the customer wallet. The industry's embrace of "all you can eat" tariffs means there are no gains to be had from more data usage by customers, which simultaneously requires Vodafone to invest in better networks. Competition is driving down prices. Like a gangster's bloodied head in the movie Casino, profit margins are inescapably stuck in a vice.

This is a fair description of the European telco in general, but Vodafone has underperformed competitors in some of Europe's biggest markets. Service revenues last year fell 5.4% in Spain, 2.9% in Italy and 1.6% in Germany, where a botched IT job was previously blamed for customer discontent. With growth of 4%, the UK stood out as Vodafone's only European success, but operators there have been able to increase prices at the uniform rate of inflation plus 3.9%. Rivals in other markets are known to be stunned this was allowed.

Even in the UK, though, Vodafone's bosses routinely grumble that its return on capital employed (ROCE) is below its weighted average cost of capital. In June 2022, a report from Barclays showed Vodafone's ROCE had been on the slide for years in Italy and Spain, too. Only in Germany, home to fewer big mobile networks, had it seen any kind of improvement.

For years, Vodafone has been abandoning parts of the empire it built around the turn of the century, and its retreat – under current CEO Margherita Della Valle – has now reached Europe. The process began in 2013 when it sold a 45% stake in Verizon, a giant US telco, for $130 billion. Most proceeds were returned to shareholders. Some were injected into network improvements under the Project Spring banner. But this now seems like ancient and forgotten history.

The other huge market it has effectively quit is India. Under former boss Arun Sarin, it spent $1.5 billion on a 10% stake in Bharti Airtel, now India's second-biggest operator, in 2005 before acquiring a majority stake in Hutchison Essar, then India's number-four telco, for roughly $11 billion in 2007. But India was ultimately a miscalculation. In 2018, after years of tax-related disputes with hostile Indian authorities, it agreed to merge Vodafone India, wholly owned since April 2014, with Idea Cellular. The resulting Vodafone Idea is the smallest and sickliest telco in today's three-player mobile market. Vodafone's stake, meanwhile, shrank from 47.6% in 2022 to 32.3% last year.

Not content with exiting countries, Vodafone is also divesting regional infrastructure. It has parked its European towers, the hat stands for its mobile network equipment, in a separate company called Vantage Towers, now listed in Frankfurt. The idea is that Vantage leases space on its towers to other telcos. Its share price has risen 41% since it first traded publicly in April 2021. By the time of the last annual report, Vodafone had reduced its indirect stake in Vantage to about 57%, pocketing capital from the sale of shares. But this has evidently done little to boost Vodafone's fortunes.

To Europe, then, where the latest deal-making under Della Valle means Vodafone exits from both Italy and Spain and a hoped-for merger of its UK business with that of Three, the smallest of the country's four mobile network operators. This will leave Germany, where service revenues squeaked up just 0.3% for the recent third quarter, as Vodafone's only big remaining market on the European continent. Its jumble of other, much smaller European assets accounted for just 13% of group service revenues for the first half of the current fiscal year. Nor does their growth trajectory buck the trend.

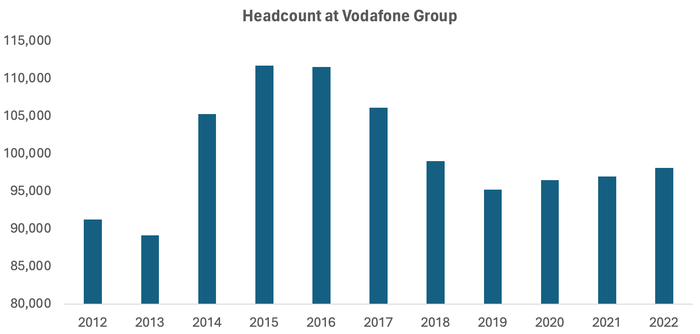

Della Valle is effectively the surgeon amputating body parts while the disease continues to spread. There has been no stock-market celebration of her latest moves. In the year she has led Vodafone, its share price has dropped almost a third. Despite hacking off limbs, it looks overstaffed, employing more than 98,000 people in March 2023, about 7,000 more than it had a decade earlier. Revenues per employee were about $466,000 in that recent fiscal year, about $20,500 less than it made in 2012 (applying the same exchange rate). Verizon, over roughly the same period, has grown its equivalent figure by $537,000, to $1,168,500.

(Source: Light Reading, Vodafone)

Technology for technology's sake

Perhaps more than any other big telco outside North America, it has become distracted by technologies and technological trends that will do little to boost sales and barely reduce costs. Financial analysts tuning in for an Nvidia update have good reason to be interested in CEO Jensen Huang's latest thoughts on the graphics processing units (GPUs) that have earned him billions. The same cannot be said for Vodafone's proselytizing about 5G, a network improvement that is largely irrelevant to customers. Even more baffling are network APIs, an attempt to make developers pay for network features of questionable value, and open RAN, aimed at cultivating alternatives to big kit suppliers.

Determined to be less reliant on third parties, Vodafone has added thousands of software engineers to its staff ranks, seeking a role in technology development. But to what end? Operators spend paltry sums on research and development, and Vodafone does not even disclose the figure in financial reports. Unlike a few Asian operators, it has no stated ambition to commercialize technology products as opposed to consumer services. Technology partners have a right to be confused. A big software investment would seem like a misallocation of funds by a company whose main priority should be customer service. A small investment would seem pointless.

The future may bring more asset disposals. But while networks may change hands or increasingly be shared, they have become too important to vanish. A safe prediction is that a mixture of Big Tech and private equity will keep advancing as Vodafone manages its decline. Network software ends up being run on Nvidia's GPUs or other advanced chips in facilities owned or managed by an Amazon or Microsoft. Fiber and radios – as well as ducts, poles and towers – are leased and shared with rivals.

Vodafone becomes the spectrum-holding middleman between all that and the consumer. It's an important job, demanding some involvement in network operations as well as attention to customer service, tariffs and various sales and marketing activities. But the Internet giants could feasibly do it just as well, bundling connectivity with their other products, and they lack only the spectrum that telcos have paid so much to license. It's a sobering thought for any telco boss.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

_International_Software_Products.jpeg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)