Big Tech, IT and telecom vendors axed 70,000 jobs last year

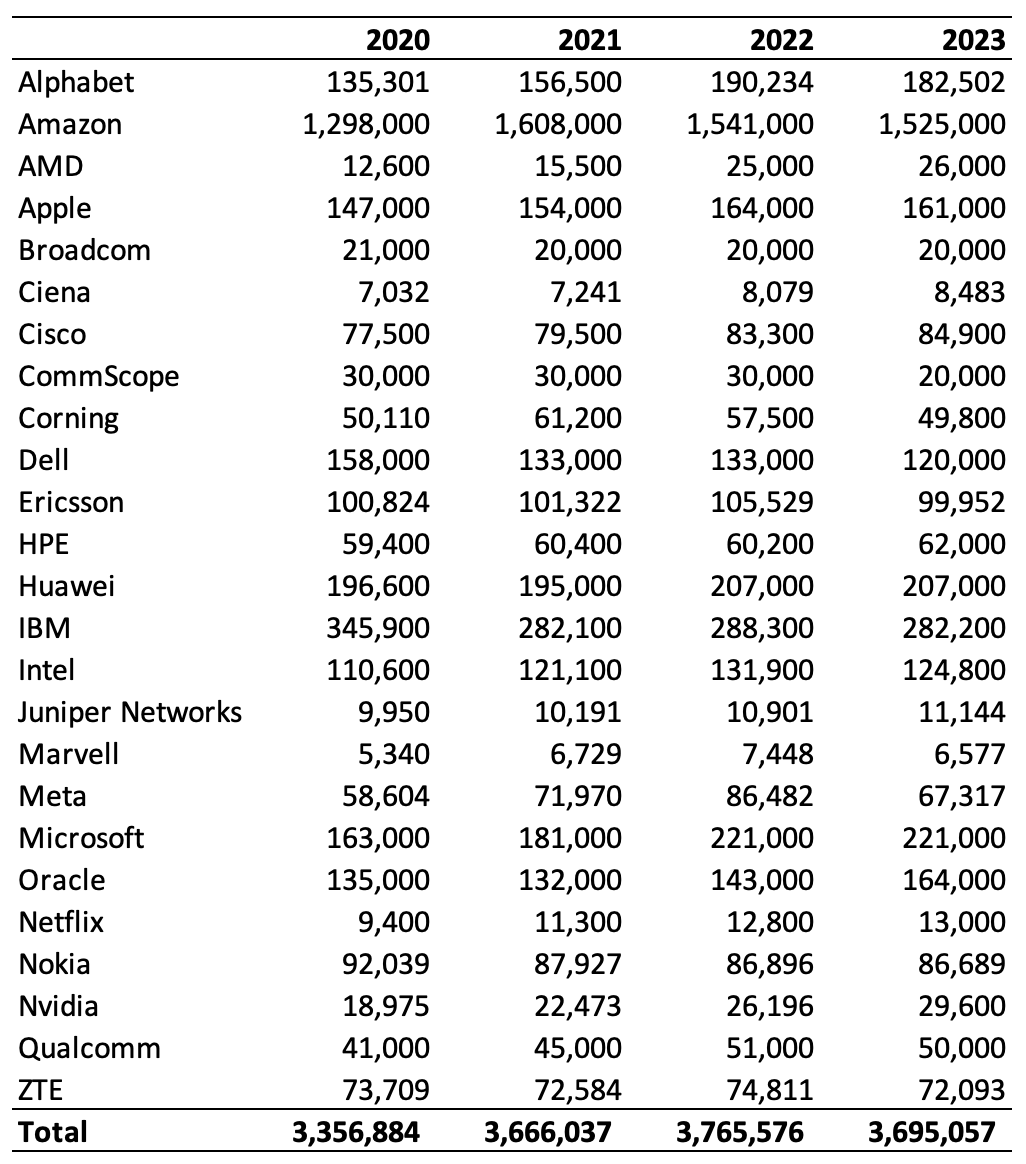

Data in the earnings reports and SEC filings of Big Tech, IT and telecom vendors shows the toll of headcount reductions in 2023.

It's apparently good etiquette, when you're the CEO of a publicly listed company, to acknowledge the hard work of your employees every so often and say things like, "MegaCloud wouldn't be anything without its people." But the people didn't seem quite so foundational in the technology sector last year. Tens of thousands lost their jobs, the data shows, and many parts of those jobs can now be fully automated, if the right investments are made. "MegaCloud wouldn't be anything without its machines, but some people still have their uses," might be more honest in the future.

Even so, for all the conjecture about automation and the impact artificial intelligence (AI) could have on jobs, recent workforce shrinkage has other causes. Technology providers, and especially the cloud companies, went on a hiring spree when the pandemic struck and everybody became an Internet addict overnight. As people crawled back outside and city centers enjoyed a brief revival, the tech sector convulsed and layoffs soon followed. The toll now shows up in recent filings with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Yet the real takeaway from an analysis of headcount over several years is that Big Tech remains dramatically bigger than it was immediately before COVID-19. Conversely, the workforce at various older technology players, including a few that serve the telecom industry, is being steadily eroded by the tides of technological change and some blustery business headwinds.

The forces at work

The contrast is sharpest between the big Internet stocks, on one side, and a collection of European and US telecom vendors, on the other. Alphabet (Google's parent), Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft and Netflix, collectively cut nearly 45,500 jobs in their most recent full fiscal year. Since 2020, however, they have added more than 358,500, bringing total headcount to nearly 2,170,000. Excluding Amazon, which accounts for 70% of that figure, job numbers fell by around 29,700 last year but have grown by 131,500 since 2020.

It's a far gloomier tale on the telecom side. CommScope, Corning, Ericsson and Nokia, four suppliers to some of the world's biggest telcos, shed nearly 23,500 jobs last year as large customers spent less. Headcount is down by around 16,500 since 2020, after sharp growth at Corning in 2021. And the outlook is bleak. Struggling with debt, CommScope seems to be on a downward spiral. It cut 10,000 jobs in 2023, according to SEC filings – about a third of the former total – and its share price has collapsed, losing 80% of its value in the last year. Nokia expects to employ around 74,500 people after it has finished its current round of cuts, down from about 86,700 last year.

(Note: numbers are for the last full fiscal year, the dates of which differ. Source: Light Reading/companies)

The big exception is Huawei, seen by Western critics as a Chinese security threat and plunderer of US intellectual property. Despite US sanctions and a European backlash against the company, Huawei gained 12,000 employees in 2022, giving it a workforce of 207,000 that year. The number was unchanged in 2023, according to its recently published annual report. Restrictions have not been as effective at hindering Huawei's progress as the US had hoped. Even ZTE, a smaller Chinese vendor, cut 2,700 jobs last year, finishing 2023 with about 72,000 employees, a drop of 9,400 compared with the total in 2016.

IT and networking companies active in telecom but doing much of their trade in other markets appear to be somewhere between the extremes. PC and server maker Dell cut 13,000 jobs last year and – with its 2023 workforce of 120,000 people – has 45,000 fewer employees than it did in 2019. But the headcount across organizations including Cisco, HPE and Juniper (with HPE and Juniper planning to merge) has grown since the pandemic, albeit not at Big Tech rates.

Intel's woes

For staff at chipmaker Intel, however, 2023 brought a net workforce reduction of 7,100 jobs. Profits have tanked because of market share losses, a downturn in customer spending on equipment (explained partly by the earlier build-up of inventory that happened after the pandemic) and investments in new foundries designed to challenge the Asian giants of TSMC and Samsung. Big Tech moves to build in-house chips that can substitute for Intel's central processing units are among the problems Intel faces.

Rather like Alphabet, Intel still seems to employ more people now than it did in the first year of the pandemic (Alphabet's headcount grew from about 135,301 in 2020 to 182,502 in 2023, while Intel's has risen from 110,600 to 124,800 over this period). But similarities with Big Tech end there. Intel's profits have collapsed, just as they have at the mobile networks business group of silicon customer Nokia, and it is at risk of displacement by chip rivals in important markets. Competitors to Amazon, Google and Microsoft are nowhere.

Essentially, a drop in sales and the need to protect profits has forced Intel and the telecom vendors to lay off staff recently. But unless staff have been employed unnecessarily, those cuts may endanger the competitiveness of the organizations making them. Big Tech layoffs do not seem to pose the same kind of threat.

Despite reports of job cuts since the end of its last fiscal year, Microsoft last week managed 20% year-over-year growth in third-quarter net income, to around $21.9 billion, on 17% growth in sales, to $61.9 billion. Future headcount reductions may help pay for Microsoft's multi-billion-dollar splurge on AI and the data centers needed to train the technology. But few expect cuts to slow Microsoft down.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like