In the year since the takeover, UnaBiz CEO Henri Bong has been slashing costs, shredding the old business model and eyeing convergence with other IoT technologies.

"Quelle horreur," seemed to be Emmanuel Macron's initial reaction when Singapore's UnaBiz offered to buy Sigfox, a French Internet of Things (IoT) specialist, last year. The French president was seen as a friend of Ludovic Le Moan, Sigfox's co-founder and former boss, who had talked up his business as a future unicorn and French technology champion. Now it risked falling under the ownership of an Asian company it had helped spawn.

Sigfox had been teetering on its baby unicorn hooves for years. Le Moan had fallen out with many of his original lieutenants and upset network operators, his effective licensees, with his demands for a huge cut of their sales. Above all, he had failed to realize his vision of connecting hundreds of millions of smart meters, temperature monitors and sensors to Sigfox networks. Burning quickly through funds, after raising about 350 million euros ($377 million) in total, Sigfox had registered only about 20 million connections when it filed for insolvency in January 2022, its immune system unable to cope with the economic fallout from COVID-19.

Enter Henri Bong, UnaBiz's CEO and co-founder, cast as a white knight in parts of the French press, despite the political objections. Based in Singapore, Bong was almost an accidental savior. He had not, at first, set out to buy his licensor, casually telling French reporters that Sigfox would not be allowed to disappear. But newspapers jumped on the story of a potential UnaBiz takeover before Bong had even run the idea past his board. His phone would not stop ringing as Sigfox customers and other operators asked if it were true.

UnaBiz eventually overcame French political opposition, seeing off a challenge from eight other bidders, including Actility and Semtech, and paying about €25 million ($27 million), according to a reliable source, for Sigfox. Bong had not expected to win, describing UnaBiz as the smallest of the nine bidders. But Sigfox's own surviving employees seemed to be on his side, regarding Bong as a member of the family. That helped in a jurisdiction where the views of staff are considered by the tribunal deciding on a deal. Many customers were equally positive, telling the president of the tribunal they preferred UnaBiz to other suitors.

To convince Macron that UnaBiz would not somehow de-Frenchify Sigfox, Bong addressed an open letter directly to the French president, emphasizing his own French connections (which included a five-year stint at the French Trade Commission). France's political establishment feared a loss of French ownership. They also worried about the ramifications for jobs in France, even though Sigfox's workforce had been shrinking from its peak of 450 employees. Bong had to make some promises.

Those included keeping intellectual property in France and securing the permission of French authorities for any subsequent sale. UnaBiz would continue to invest in France for at least the next ten years, Bong assured Macron. He would also safeguard French jobs that appeared to be at risk. When the deal went through, the formerly profitable UnaBiz looked to have saddled itself with a loss-making business, pitching a technology that few organizations wanted.

A brief history of UnaBiz

Bong may have felt he had little choice. He first encountered the Internet of Things and the concept of low-power, wide-area (LPWA) connectivity during his days at the French Trade Commission. Technologies including Sigfox, LoRa and Britain's Neul were using unlicensed spectrum to provide low-cost connectivity for unglamorous tracking devices that needed bits, not gigabits. This was the other end of the market from superfast smartphones and one that cellular's stakeholders had largely neglected since the 2G era. Intrigued, Bong soon found himself working for Sigfox.

Back then, the company had just secured about €150 million ($162 million) in funding and was on a high. But it lacked a presence in Asia. Invited by Le Moan to take charge of regional development, Bong hired the first 25 employees based in the Asia-Pacific and began courting prospective customers and licensees. Anyone could build a Sigfox network if they signed up to its stringent obligations. These included sourcing equipment from Sigfox, meeting strict coverage targets and sharing 40% of revenues with Sigfox. Because people were convinced the market was on the cusp of an IoT boom, nobody seemed to worry.

Bong decided to get out in 2016. He harbored doubts about Le Moan's target of supporting a billion or more device connections by 2020. With only tens of millions, Sigfox would struggle to generate profits by charging as little as $1 or $2 per device each year for connectivity, as it claimed it could. But he was persuaded to become a Sigfox licensee for Singapore and Taiwan, geographically small countries that would be easier to cover. With Taiwan, Bong would also have access to a vibrant electronics ecosystem. UnaBiz was born that year.

UnaBiz CEO Henri Bong (center) alongside executives from ZifiSense, another IoT company.

(Source: UnaBiz)

It quickly discovered it could not make enough money by selling just connectivity. Bong pivoted to hardware, drawing on his connections with electronics companies, and by 2017 had produced UnaBell. Described as a "smart button" suitable for numerous applications, it cost as little as $10 per unit at a time when Bong reckoned most rivals were charging $60 to $80. Series A funding followed the next year from KDDI, one of Japan's biggest telcos, along with French energy firm Engie. And then came Nicigas.

The Japanese energy company was trying to install smart meters in customer homes. But it had encountered two big problems. One, most of the available hardware was far too expensive. And two, Nicigas lacked its own management platform. Through a subsidiary called Soracom, itself a Sigfox investor, KDDI had offered to build that platform and transfer ownership to Nicigas. Bong was asked if UnaBiz could tackle the hardware side, delivering a smart meter at a unit cost of less than $30. "We signed up for 850,000 units and the best thing is we deployed them in 18 months in COVID time," he said.

Project clean-up

UnaBiz's hardware role and partnerships meant that – unlike most Sigfox licensees – it was involved in other technologies. In Japan, the Nicigas smart meters were operating partly on a cellular network in areas that Kyocera, the local Sigfox operator, did not cover. Nevertheless, Sigfox's disappearance would have been a disaster for Bong and other licensees. By the time Sigfox filed for insolvency, UnaBiz was recording profits, according to Bong, and it had just raised another $25 million – a strikingly similar sum to the amount it apparently paid for Sigfox – in a Series B funding round led by SPARX, a Japanese investment group.

An acquisition that looked necessary for survival quickly turned into project clean-up. Sigfox was burning through up to $80 million a year, says Bong, and it had reported annual revenues of just €60 million ($65 million) back in February 2019, a year before COVID struck. Of its roughly 100 employees outside France, as few as 10 were retained. Today, UnaBiz, including Sigfox, employs around 220 people worldwide.

Elsewhere, Bong took a sharp axe to costs. One of the first things to go was Sigfox's lavish office near the Champs-Elysees in Paris, premises that were costing Sigfox about half a million euros a year, Bong reports. The WeWork facilities into which staff subsequently moved were available for just a tenth of that amount. Bong also cut down on half the office space in Toulouse, where Sigfox had its headquarters.

Not the cheapest neighborhood in Paris.

(Source: Cedric Chan under Creative Commons)

In France, where Sigfox owns and operates a network comprising 2,600 basestations, there have also been renegotiations with towers companies, including Cellnex and TDF, the providers of the passive infrastructure on which Sigfox hangs its equipment. Rental costs have been slashed by as much as 70%, claims Bong. Separate renegotiations with AWS and Google, Sigfox's public cloud providers, have saved it up to 60% on what it was previously paying, he told Light Reading.

Despite these efforts, the once-profitable UnaBiz chalked up a $17 million net loss last year, although this was better than the $20 million it had been expecting (Bong declined to share a figure for annual revenues). This year, it aims to shrink the loss to about $10 million before breaking even in 2024.

Open marriage

The controversial business model has been shredded and replaced, too. During a September meeting in Labège with about 70 of Sigfox's operators, many of whose bosses were previously unknown to Bong, the UnaBiz CEO promised a different sort of French revolution and a more collaborative ethos. Out went the demand for a 40% cut of operators' service revenues. In its place is a formula (undisclosed to Light Reading) based on traffic levels. But operators are also no longer held to ambitious national coverage targets before they have even signed contracts. Henceforth, they can build at the pace they deem appropriate.

Another innovation was to make UnaBiz a purchasing center for solutions, building on the Singaporean company's experience in the hardware field. Instead of having each operator negotiate separately for components, UnaBiz can drive scale economies through bulk buying and feed improved margins back to its partners. For Bong, much of the revenue opportunity is in developing bespoke solutions for clients, and not just providing connectivity. While he is coy about sales figures, he claims to generate about 60% of his revenues today from these solutions.

Arguably the biggest change of all, though, has been allowing Sigfox operators to have an open marriage. When Le Moan was in charge, they had to be faithful to Sigfox. Today, they can mess around with other network technologies as much as they like. There is a risk this constrains the outlook for Sigfox if operators decide LoRa or NB-IoT – a cellular response to Sigfox – is just as good if not better. But technology agnosticism is part of Bong's playbook, and he even dreams of uniting Sigfox with LoRa and other options in some grand LPWA standard.

All this is partly about improving Sigfox's lousy reputation. "Sigfox has been cornered as a proprietary technology, as a company so arrogant it doesn't want to work with anyone," said Bong. "We need to change that." As a start, he has been striking deals with LoRa providers including Actility, Senet and The Things Network to support international roaming. With Sigfox more widely available in some countries, and LoRa ahead in others, this joining-up of footprints could suit customers bothered by the previous lack of global LPWA connectivity.

The Nicigas rollout of smart meters was a major early deal for UnaBiz.

(Source: UnaBiz)

"LoRa and Sigfox are actually very compatible, using the same antennas and more or less the same chipsets and transceivers and so it's just a question of the module on the MCU [microcontroller unit] and what software-defined radio you put it on," said Bong. "We can imagine a future where devices speak several languages and just by a downlink you can switch from LoRa to Sigfox or to a new technology. That is possible, so why not build together?"

In a step toward full technology convergence, UnaBiz has also worked separately with Senet and Actility to create application programming interfaces (APIs) that provide links between their different clouds and back-end systems. A sterner challenge, Bong concedes, is developing basestations that can support multiple technologies. "It's not that simple. It's another step. The first thing is on the software part and the cloud and the second is on sensors."

His market also lacks an equivalent of the 3GPP, the standards body where giant cellular vendors pool intellectual property and thrash out the relevant licensing arrangements. In its absence, vested interests trying to defend their own turf could thwart attempts at convergence, Bong concedes.

One thing that differentiates Sigfox from Semtech, the chips company perceived to be the powerbroker in LoRa, is free access to intellectual property, insists Bong. Following the various deals with LoRa providers, UnaBiz made another big move when it opened up Sigfox's device library codes. Today, that allows any chipset company or device maker to build Sigfox products without paying royalties to Sigfox.

The connectivity conundrum

But having so clearly staked his company's future on connectivity and solutions, Bong needs to show that connections are growing – if not to the interstellar levels envisaged by Le Moan then at least to much higher numbers than Sigfox managed under its former boss. UnaBiz has given up the dubious practice of reporting registered connections as opposed to active connections, one that led to massive inflation of Sigfox's figures. But the active connections as recently as April totaled just 11.4 million worldwide.

The good news is this was 16% more than it had a year earlier, and Bong says the current rate of growth is even higher. "Customers are not leaving, and large customers like Securitas, Verisure and Nicigas keep deploying. We can see an increase every month." The earlier rate of growth, he says, is not markedly different from what other LPWA technologies have seen.

For a long time, the chief concern for Sigfox, LoRa and other LPWA variants has been that a cellular assault through NB-IoT and another standard called Cat-M – will eventually "crush" them, as erstwhile Vodafone executive Matt Beal threatened back in 2016. Years later, it is still unclear if Sigfox and NB-IoT are trading blows or in entirely different weight categories, as Sigfox formerly claimed. But outside China, where the government has given NB-IoT a huge push, the cellular technologies have had their own growth problems, and Bong thinks China's priorities have recently changed.

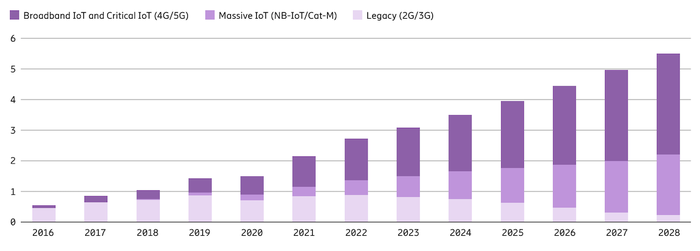

Cellular IoT connections by segment and technology (billions) (Source: Ericsson, GSA September 2022)

(Source: Ericsson, GSA September 2022)

"NB-IoT was performing well when the central government was subsidizing it, and now they are subsidizing only 5G," he said. "It is forbidden now to deploy it in China and it has to be sold overseas." Meanwhile, the cellular operators not in China, once antagonistic toward anything conceived outside the 3GPP, are more receptive than ever to other technologies, he believes. "After eight years in the market, we see these guys coming back to us."

Sigfox was obviously in terrible shape before UnaBiz came to its rescue. For years, it had suffered mismanagement under Le Moan, obstinately clinging to a business model that had alienated partners and failed to boost growth. Bong comes with an openness and apparent honesty that had been missing before. And while UnaBiz brings no guarantees in such a cutthroat and low-cost industry, an overhaul looked overdue. Its new owner has certainly delivered that.

Related posts:

— Iain Morris, International Editor, Light Reading

Read more about:

EuropeAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like